Yom Kippur and the unique ceremony of the two goats

The scapegoat in Leviticus is the opposite of a “scapegoat” as we use the word today when we blame someone else for our troubles

This series of articles by My Evven and ALL ISRAEL NEWS aims to rediscover forgotten events, traditions and places in Israel.

To learn more about My Evven click here. Use checkout code ‘AllIsrael’ to receive a 10% discount for your purchase and become an Evven (‘stone’ in Hebrew) Guardian.

The holiest day of the Jewish year – Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement – occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the seventh month of the Jewish calendar.

In 2022, this falls on Wednesday of this week. The observance of Yom Kippur will begin on Oct. 4 at sundown and will end at nightfall on Oct. 5.

“The Lord said to Moses, the tenth day of this seventh month is the Day of Atonement. Hold a sacred assembly and deny yourselves… Do not do any work on that day, because it is the Day of Atonement, when atonement is made for you before the Lord your God… You shall do no work at all… and you must deny yourselves.” Leviticus 23: 26

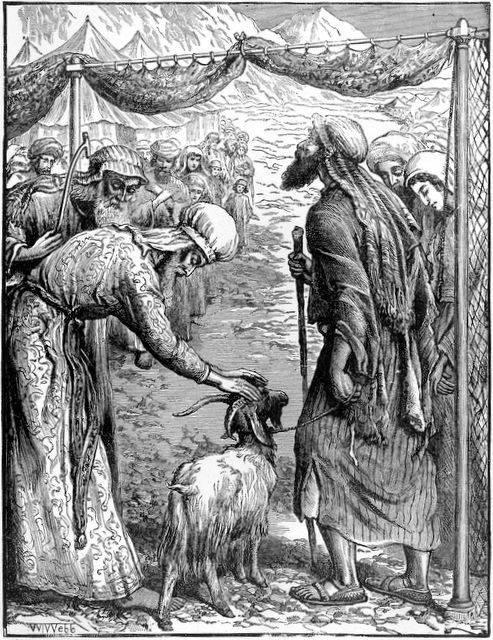

Leviticus 16 describes the service to be carried by the High Priest in the Temple during this day. The strangest element of the service was the ritual of the two goats – one offered as a sacrifice, the other sent away into the desert.

“Then he is to take the two goats and present them before the Lord at the entrance to the tent of meeting. He is to cast lots for the two goats—one lot for the Lord and the other for the scapegoat. Aaron shall bring the goat whose lot falls to the Lord and sacrifice it for a sin offering. But the goat chosen by lot as the scapegoat shall be presented alive before the Lord to be used for making atonement by sending it into the wilderness as a scapegoat.” Leviticus 16:7

The two goats that were brought before the High Priest were chosen to be identical and indistinguishable from one another. Lots were drawn, one bearing the words “To the Lord,” and the other “To Azazel.” The goat on which the lot “To the Lord” fell was offered as a sacrifice. Over the other goat, the high priest confessed the sins of the nation, and it was then taken away into the desert hills outside Jerusalem where it plunged to its death.

Sin and guilt offerings were common in ancient Israel, but this ceremony was unique in almost every aspect. Normally confession was made over the animal to be offered as a sacrifice. In this case, confession was made over the goat not offered as a sacrifice.

Numerous explanations were offered by the sages for over a thousand years. The following is an extract from an explanation offered by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks:

It is clear that sins cannot be taken off the shoulder of one being to be laid on that of another being (e.g., a goat). The ritual of the two goats has a symbolic character that was intended to impress men and to induce them to repent.

A major theme of the Bible is the contradiction between monotheism and polytheism. In polytheism, there is a continuous conflict between different gods that represent or are known for different characteristics.

In monotheism, all characteristics and even tensions – between justice and mercy, retribution and forgiveness – are found within one God. With this single shift, the conflict between two separate external forces is re-conceptualized as internal, psychological conflict between two moral attributes.

Perhaps the two goats, identical in appearance yet opposite in fate, symbolize the duality of our nature. We have within us two inclinations, one good and one bad. Instinct leads to evil, but we can conquer it, as God told Cain: “Sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you can master it” (Genesis 4: 6).

We can face our faults because God forgives, but God only forgives when we face our faults. We face our faults by confessing them, and the confession itself represent the duality of our nature, since if we were only evil, we would not confess, and if we were a hundred percent good, we would have nothing to confess.

However, it is hard to rid of the feeling of defilement once you have committed a wrong, even after it has been forgiven. The scapegoat departure is a visible representation intended to help us feel that defilement has gone away.

The scapegoat in Leviticus is the opposite of a “scapegoat” as we use the word today when we blame someone else for our troubles. By confessing the nation’s sins over the goat before sending it away to the desert, we accept responsibility instead of blaming others.

And so I leave you with the traditional Hebrew greeting said before Yom Kippur, which translates as “a good final sealing,” in the Book of Life, G’mar Chatima Tova, in which we pray that our names, inscribed on Rosh Hashanah are sealed on Yom Kippur.

Uri Steinberg is a former Israeli Tourism Commissioner for North America, Israel Ministry of Tourism, and currently serves on the ALL ISRAEL NEWS advisory board.