New book focuses on rabbis' prayer in the White House

The U.S. Congress opens each session with a prayer offered by a chaplain or guest chaplain. Among the guest chaplains: Rabbis.

Editor's note: Joel C. Rosenberg has known Howard Mortman for more than 25 years. Mortman is a director for communications at C-SPAN and he has just published a book that offers a unique insight from Washington D.C.

The U.S. Congress opens each session with a prayer offered by a chaplain or guest chaplain. Among the guest chaplains: Rabbis.

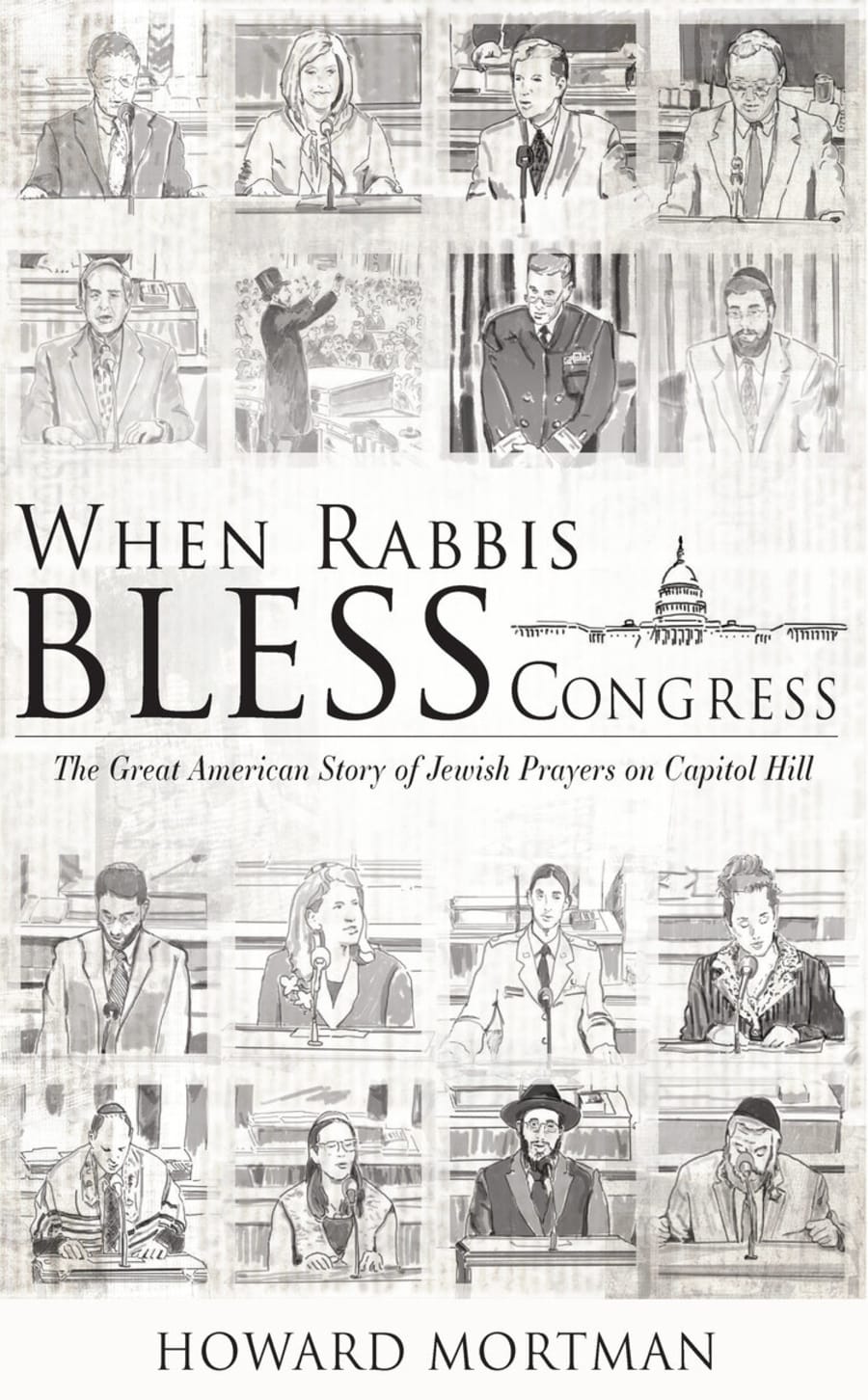

Howard Mortman’s new book When Rabbis Bless Congress: The Great American Story of Jewish Prayers on Capitol Hill is about the rabbis. It’s an unprecedented examination of 160 years of Jewish prayers delivered in the literal and figurative center of American democracy. With exhaustive research written in approachable prose, it uniquely tells the story of over 400 rabbis giving over 600 prayers since the Civil War days—who they are and what they say.

The following is an excerpt:

Need more prayer in your life?

Simple solution: Just turn on your television and watch Congress.

The unlikely congregation is the backdrop for a taxpayer-funded ritual dating back to our country’s creation. Every session of both legislative bodies— the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate—opens with a prayer. The Divine gets his due even before the flag gets a pledge.

This tradition might bother some. You may not like the idea of Congress incorporating religion into its official proceedings. You may not want the Congressional Record reading like a prayer book. You may seek policy debate on your TV or internet stream and instead get two minutes of unsolicited religious teachings. Or perhaps you think it’s all fine, nothing wrong, no problem with prayer in a public forum. Of all the things Congress does day in and day out, praying to the Almighty ranks among the least offensive. Either way, the fact is: Prayer happens. It’s part of Congress, its past, present, and likely future. Just like floor debates and votes. And it’s a tradition upheld by the Supreme Court which, despite Moses the prophet’s prominence outside on its building—depicted on top, in front, in center on the East Pediment—inside does not open in prayer.

Nearly every prayer in Congress invokes God. Many are in Jesus’ name. And some are Jewish.

Hundreds, actually. As of February 2020, 441 rabbis from over 400 synagogues have opened Congress—increasing at an average rate of 7.5 Jewish prayers per year since World War II.

This is the story of rabbis who have led Congress in prayer. Who they are and what they say. Their connection to America’s politics and policy and history.

Christians have been praying in Congress since the Revolutionary War ended. Jews, since right before the Civil War began. And along the way, some great history, lofty inspiration, notable quirks, plus idiosyncrasies and even cringeworthy moments, language, and personalities, which might have seemed correct at the time but hold up poorly against today’s standards. Few of the prayers are dry. There’s character and narrative behind most of the rabbis.

Of the first rabbi guest chaplain, in 1860, a member of Congress said: “I was pleased with his appearance. I should like to see our Chaplain officiate in costume.” The New York Times noted the “learned Rabbi, who appears in full canonicals.”

Nearly a third of the rabbis are, as you might expect, New Yorkers. But they’ve also represented many states without many Jews. Like Alaska.

Rabbis reflect immigration patterns, the American story. They come from 24 countries other than America. In the early days they were part of the well-documented immigration from European countries. Now immigrant rabbis have Latin American roots. The first Latin America-born rabbi to open Congress in prayer did so a year after becoming a U.S. citizen.

Six rabbis who survived Auschwitz have opened Congress in prayer—and 13 post-Holocaust guest chaplain rabbis were born in Germany.The record for the greatest number of prayers given by a single rabbi is held by a Navy chaplain.

A president once invited a rabbi to open the House in prayer in order to prevent war with Britain. A rabbi prayer less than a week before Pearl Harbor warned of “dark forces of tyranny and oppression” and “encircling gloom.” The day before D-Day, another rabbi asked God to be “with our armed forces on land, on sea, and in the air.”

Isaiah is the big winner in rabbi prayers: Over one out of every ten rabbi prayers cites him. Three rabbis didn’t mention God. The American historical figure mentioned most in a rabbi prayer? George Washington. The most mentioned American Jewish historical figure? The Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

Want to hear rabbis cite Moses and Scripture and Torah and Talmud and Mishnah to legislators and the public? Don’t turn to Jerusalem—the Knesset does not open with prayer (although, arguably, who in the Knesset isn’t a rabbi?). Instead tune into Washington, where Israel’s chief rabbis can and have served as guest chaplains in Congress, just like hundreds of others.

You’ll find in the center of the nation’s capital, on a hill, at the front of each chamber of Congress, a story of Jewish contribution to American democracy that’s been well over a century and a half in the making but only now being told.

Howard Mortman is author of When Rabbis Bless Congress: The Great American Story of Jewish Prayers on Capitol Hil, published in October 2020 by Academic Studies Press. More information here.