How to revive a language

Hebrew is the only language in the world that has ever been revived from a dead to a living language. Many people, like the Irish and Scottish, and many indigenous groups in the Americas and Australia, have wanted to do the same but failed. Reviving a language to go from a non-spoken language to a common spoken language is almost impossible, but if we want to take a look at how it’s done, the world has a test case of exactly one.

That’s pretty incredible. One would almost say… miraculous?

So, how did it happen, and why was it possible? Many people point to Eliezer Ben Yehuda (1858-1922) as the reviver of the language. Well, he was definitely an important figure, but he wasn’t alone. He couldn’t have done it without a critical mass of people who believed in the same dream as him, and he couldn’t have done it without the history of Hebrew usage throughout the centuries.

One of the big challenges people ran into was that the existing material in Hebrew was mostly religious. How do you describe modern phenomena, new inventions, and machines with a language that hasn’t been spoken for thousands of years?

Well, you don’t. Because when I described Hebrew as “a language that hasn’t been spoken for thousands of year” I lied. Hebrew has been widely spoken in an unbroken chain from the time of the Bible until today. It just wasn’t a mother-tongue for a long time. But it was used, spoken, written, and utilized a lot. And in the 1800s people already started to make up new words for modern phenomena. The first Hebrew periodical newspaper, haMe’assef, was established in Koenigsberg (today Kaliningrad) in 1784.

How come there were newspapers in Hebrew in East Europe in the 1800s? The European enlightenment had ignited a Jewish enlightenment called the haskala, or the maskilic way of thought. They rejected Yiddish and advocated for Hebrew, and established Hebrew newspapers. The National Library of Israel explains on their website: “A relatively large number of Hebrew readers existed, and it began to develop as a modern language. As a result, during the 1850s, Hebrew newspapers and periodicals began to be published that emphasized news reports and enjoyed a long lifespan (Ha-Magid, Ha-Melitz, and more). These new media were used not only by the Hebrew maskilic stream of Judaism, but also by the competing stream, the Haredi Orthodox movement (Ha-Levanon). When the seeds of Jewish nationalism began to appear, several maskilic newspapers sided with the new movement, and new papers were founded supporting its ideology. The development of the small Jewish community in Palestine as an ideological center was also expressed in the development of the Hebrew press there (Ha-Levanon, Habazeleth, and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s newspapers).”

See, even if Hebrew was no one’s mother tongue in the early 1800s, it was still a language used as a lingua franca when Jewish communities from different parts of the world communicated with one another. You might think of Yiddish as a Jewish language, but it was an Ashkenazi language, limited to Europe. The Jews in the Middle East would speak Ladino or Judeo-Arabic. If they wanted to communicate, and debate or get aligned about religious questions, what would be more natural than using the Hebrew that they all learn in any case for reading the Torah and praying from the Siddur? Except for some isolated Jewish communities in Ethiopia and India, most Jewish communities worldwide had intense and continuous contact with one another.

Now, let’s take the word for “machine” as a good example. The Modern Hebrew word is “mechona” (with the ch pronounced in the throat as in German). We can already see the similarity to “machine,” right? Yet, it’s still an original Hebrew word!

In 1 Kings 7, the book describes the temple that Solomon built, and in verse 38 it says “mechona” which means stand or pedestal, and is derived from the root KWN (the K can sometimes be CH and the W can easily turn into U or O) from which we also get words like “nachon” (correct), “hechin” (prepared) “kivun” (direction) or “hitkaven” (meant). It’s a root that conveys stability or standing still, or a fixed direction.

The only occurrence we have of the Hebrew word “mechona” after the Bible and before modern time, is when it’s used in a 4th century text as some sort of fence to keep sheep or camels in. Maybe it was a natural derivation of pedestal. It was something that keeps something in place. In any case, it had nothing to do with the Greek word “mechane.”

Because from the 5th and 4th centuries BC, the Greeks used a device called “mechane” to lift an actor into the air, made of wooden beams and pulley systems. It was particularly used to bring gods onto the stage from above, hence the Latin term “deus ex machina.” This word is the origin of the word “machine” in most European languages, and from it we get terms like “mechanics” and “mechanism.”

Again, this word’s similarity to the Hebrew word for pedestal is a mere coincidence.

But noting this similarity, the Hebrew newspapers in the 1800s decided to revive the Hebrew word “mechona” as a Hebrew translation of machine. They did this with many different words, and it would sometimes work, and sometimes not. Specifically, this word was extremely successful, because it was so useful. Having this word, you can use this in connection with another word and easily get terms for new modern phenomena. For a machine gun, you’d just use the biblical term for shooting arrows and combine with mechona, and you get “mechonat yeriya” – shooting machine. You want to write science fiction in Hebrew? The character maybe has a “mechonat zman” – a time machine. For some time the Hebrew word for train was “mechonat barzel” – iron machine. Because the word “iron” is in the Bible too. (That specifically didn’t stick).

But how do you present a new word, if Hebrew is the language you’re writing in? Well, what they often did was to present the Hebrew word they made up, and then add the Yiddish or European word for it in parentheses, for clarity. The first occurrence we have of “mechona” is in 1857. The paper “haMagid” wrote about the efficiency of the printing machine and writes “This mechona (mashine) will itself fill the work of four zetsers every day.” The word “mashine” in parentheses here was in Yiddish.

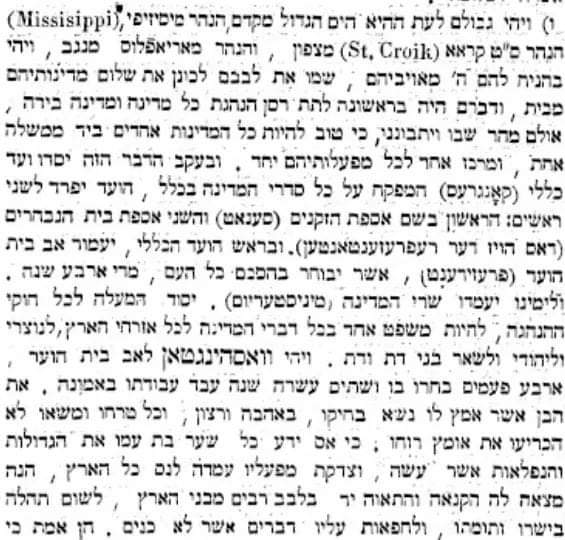

Here are two examples of what this looked like. This first one is from the “haCarmel” paper from 1861 and describes the American election system. Note how names of places like Mississippi are explained in Latin letters, while words like “congress” and “senate” or “president” first have a made-up Hebrew term for it (none of these specific ones survived), and then the original word is written in Yiddish.

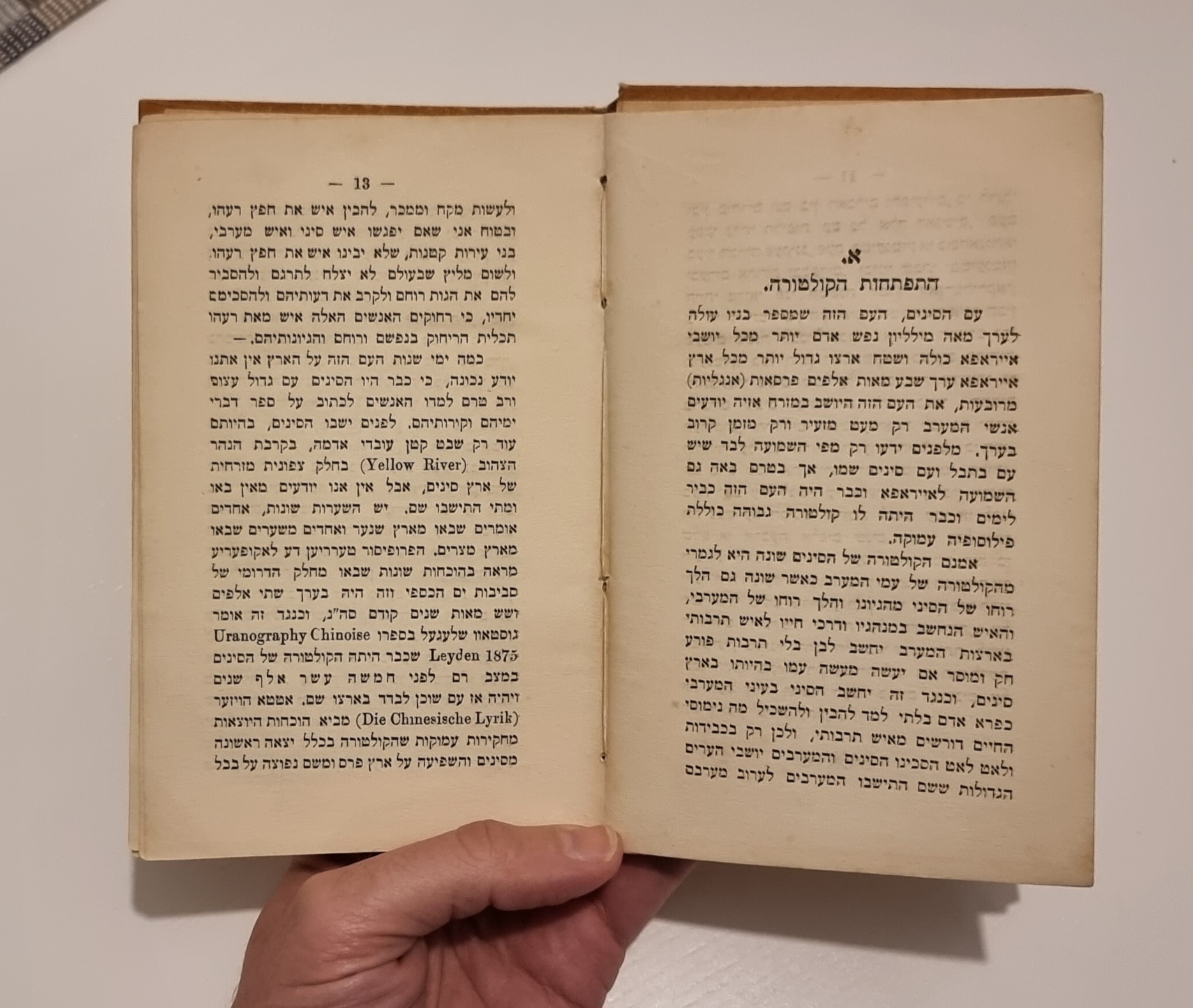

This other example is from 1911, when my great-great-grandfather, Saweli Perlmann wrote a book in Hebrew about China. From just this page here, we can see a number of differences from Modern Hebrew. Besides using the borrowed word “kultura” for culture (instead of the Hebrew “tarbut” that we use nowadays), he felt the need to add “Yellow River” in English in parentheses to make it clear what he meant, even though it seems pretty clear to me. He literally just translated the name “Yellow River” into Hebrew, but apparently he felt it was unclear. Also, it is clear that when referring to names of people and countries, he is using the Yiddish and not the Hebrew spelling. Asia with a Z and not an S, names of people using the Yiddish letter for E that is not used in that way in Hebrew, etc. This is typical of the pre-Ben-Yehuda type of published Hebrew.

But 1911 is already late – by now this type of Hebrew that relies in part on Yiddish and needs extra explanations is reaching its end, and a new era has dawned in Zion. In 1882, Ben Yehuda’s son, Itamar, was born, who became the first Hebrew-speaker from birth since biblical times. Already in the 1910s, the new Jewish schools established in Israel were taught in Hebrew only. The first non-religious Hebrew-speaking school in Israel was established in Yafo in 1905. The first one in Jerusalem, in 1909 (and my son goes to that school now). With Hebrew poets and authors working from Israel, and Tel-Aviv established as “The first Hebrew city,” the development of the Hebrew language continued from the Jewish Yishuv in Israel rather than Europe. The holocaust was, of course, another factor which brought about the final end of the European-based Hebrew, and Yiddish ceased to be a threat against the renewal of the Hebrew language.

Ben Yehuda did a lot – but he didn’t do it alone. He stood on the shoulders of over a century of modern Hebrew literature, and many centuries of fluent Hebrew-speaking Jews from all over the world. So the first rule if you ever want to revive a language on your own is – make sure there are thousands of people who already speak it, and a century or two of modern literature behind you. The second rule is to force your baby to become the first ever native speaker, and then lobby for forcing schools to teach in that language only. Also, do all this about 70 years before the new country that will use it becomes independent.

In short – you need to be a little crazy.

This article originally appeared here and is reposted with permission.

Tuvia is a Jewish history nerd who lives in Jerusalem and believes in Jesus. He writes articles and stories about Jewish and Christian history. His website is www.tuviapollack.com